RR: Something you said to me in your very first e-mail: In Firecracker, David is Jimmy's father. That’s big, Steve. Now I'm no Firecracker authority (although I may be getting there), but I never got this upon viewing the film, and when I read that, it blindsided me. I asked my friend Don, with whom I saw the film, and it also escaped him. If this was your intention, I'm not sure it comes through – and yet it puts a huge spin on the film's events.

SB: It's less important whether or not a viewer consciously thinks "Oh, David is Jimmy's father" than it is he leaves the film with an unsettling feeling about the triangle of Jimmy, David and Eleanor. Viewers who watch closely will sense the fear and sexual tension that exists between David and Eleanor and will wonder if Jimmy is a result of that, given his age and the health of Mr. White. I didn't want the average viewer to be hit over the head with a hammer with respect to this tension and the possibility of David being responsible for Jimmy's paternity. That which is alluded to is far more powerful than that which is simply stated.

SB: It's less important whether or not a viewer consciously thinks "Oh, David is Jimmy's father" than it is he leaves the film with an unsettling feeling about the triangle of Jimmy, David and Eleanor. Viewers who watch closely will sense the fear and sexual tension that exists between David and Eleanor and will wonder if Jimmy is a result of that, given his age and the health of Mr. White. I didn't want the average viewer to be hit over the head with a hammer with respect to this tension and the possibility of David being responsible for Jimmy's paternity. That which is alluded to is far more powerful than that which is simply stated.

So many of our visual stories bash people in the head with statements and it's making people brainless. Televised sports are one of the biggest troublemakers. Studio films geared towards a younger audience are the second. From a very young age we learn to watch something and not think. While we're watching sports, announcers are shouting at us to tell us what we're seeing. As if that weren't enough, after we've seen it and been told what we saw, we're shown the exact same thing again, but this time in slow motion. The announcers once again tell us what we're watching and sometimes repeat this process two or three times.

Firecracker is filled with hidden meaning, symbolism and poetry. It's one of those stories that you can find something new in any time you watch it. I've had people tell me that they didn't start fitting it together until the third time they saw it. One person said it's like an opera, or classical piece of music - with each listen a person will hear new notes, new instruments, and gather new meaning. I'm very proud that the film confronts people having to think for themselves.

RR: Mike Patton offered to do the score for Firecracker, but you turned him down. Why? Patton has such a following, that in addition to his performance in the movie, it seems that having an accomplished musician doing the score would've been a huge coup, both from an artistic and a financial standpoint.

SB: This wasn’t Evita. To say that it would be a coup artistically is incorrect. Mike’s musical aesthetic was not what I was looking for. I appreciate what he’s doing and I’m a huge fan of his personally, but I don’t like listening to his music. Ironic, eh? He did send me a Cole Porter cover he did so I could include it on the soundtrack. If we ever release one, maybe I’ll include it. But in the film, it didn’t work. I needed to have what I ended up using. His participation musically would not have changed the outcome financially.

RR: Firecracker allegedly had a $2 million budget. You tell me now that since the film has been sold, you'd like people to know that the budget was actually a little over $300,000. I understand the logic at work there, but how were you able to make this film for so little? How can you pay talent like Karen Black, Mike Patton, Susan Traylor and indeed the vast size of your entire cast and crew over an 8-week period for that kind of money? And why inflate the budget to $2 mill? Why not $1 mill?

SB: Yes, it’s always a good idea to tell your buyer your product cost more than it actually did. Many people we spoke to in the industry said our movie looks like it cost $4M. I suppose had we shot it anyplace else, and had we hired all of the work done instead of doing it ourselves, it might have cost that much. But Kansas is a right-to-work state, we did a lot of our own labor for free, all the cast was paid scale and took deferred pay, the crew were made up mostly of interns, and all the props, cars, homes, etc., were donated. We paid key personnel a little something, but compared to industry people, it’s miniscule. Have you seen the making-of documentary? Wamego: Making Movies Anywhere shows how we did it for the most part. One of the gypsy wagon trailers only cost $158. I went scouring the junkyards for free materials and built them myself. I’ll send you a budget/expense report for Firecracker, which you are free to publish (click here and here).

Obviously we had above the line expenses. Such costs as actor travel, cast compensation, cast living expenses and such were a part of the film’s overall costs. However, we did everything we could to reduce these expenses and keep them low. From deferred compensation for actors and producers to a donated copy machine to make scripts, we squeezed as much as possible on above the line costs. All “above the line” expenses equaled $20,699. I have this figure combined because some actors received more than others and some none at all.

RR: You grew up in a small town. You live in a small town. You make your movies in a small town. Both films you’ve made are set in small towns. Do you have any interest in exploring big city life in your work? Most artists can’t wait to get out of the small towns they grow up in.

SB: Most artists can’t wait to escape themselves, regardless of where they’re living. When I learned to respect myself, I realized that the message of The Wizard of Oz is a truth: if you can’t find it in your own back yard you aren’t going to find it anywhere at all.

I’m interested in exploring realities and ideas that mean something to me no matter where they happen. Being where I am is always more interesting to me than being someplace I’m not. I do not desire to be not where I am. Basically, I understand that the grass is greener when I’m standing on it. Last fall when I spent some time in Europe, I experienced some pretty amazing things. Naturally I got my notebook out and decided to develop a movie to capture those feelings. I’ll shoot that in Europe. I’ve also recently been approached by a production studio in Germany who wants me to direct a surrealist film in Munich. I think it’d be a great experience and opportunity. I’m also kicking around some projects to do here in the USA, and of course, here in Wamego.

RR: How do the other residents perceive you and what you do in Wamego? What’s the general consensus of the movie by the rest of the town?

SB: Before Firecracker came out I had a private screening for many of the local people. Many of the people who were there on the alley when they dug up the body were still alive. Several of the supporting characters depicted were based on real people who were still alive. So I had them all to see it. I was nervous they would say, “oh I never did that,” or, “that isn’t what happened,” but they were stunned, emotional and loved it. I think they weren’t prepared for it to be as dark as it was, but they all knew the story just as well as any of us who made it—after all, they lived it.

RR: Is Larry the Cable Guy big in Wamego? Do they still play reruns of Mama’s Family on the local affiliate station? (Note to readers: Having myself grown up in a town smaller than Wamego, these are perfectly valid questions.)

SB: I feel like this question is meant to assassinate my character. I don’t watch television unless it’s the evening news or something educational, like History channel or PBS. So I’m not sure what reruns play. In addition to indoor plumbing, you can get Tivo in Wamego, too, so you’re able to watch what you want.

To explain why I live in Wamego, Kansas, let me tell you the story of one of the local businesses. Half a century ago, the blacksmith started up a construction equipment business and their steel supplier was in Kansas City. One day the steel supplier said to him, “You know, if you guys are ever going to be successful, you have to move to Kansas City”. His response was that was the stupidest thing he’d ever heard, and, “we’ll show them!” Well, 40 years later when the company was sold to Caterpillar and became a subsidiary of a Fortune Top 50 Industrial Corporation, it was the largest designer, producer and seller of specialized mining attachments in the world. Today, fifteen years after CAT’s purchase, it is still headquartered in Wamego, Kansas.

RR: You seem to have an unusually supportive family, especially for a small town guy with a big vision. How much of your success do you owe to them?

SB: All of it! I was raised with these values and this outlook on life. I was taught to listen to myself instead of my neighbors, churches, governments or others. I was taught to be me and I was encouraged to trust my own instincts. Sure, there are always moments when someone’s childhood was shitty or their teen years filled with angst. But it was more interesting to be around my family and learn about my history. I come back to not having that grass is greener syndrome. Susan Traylor had the same kind of family growing up as I did. She always said her friends would beg her to go out and whatever and she’s say, “but it’s more exciting to stay at home.” And, I understand what she means!

My father has a remarkably bright sense of business and management but he has also been interested in the arts. There was a time a few years ago when he was president of the Kansas Arts Commission. When it came time for me to find investors, he knew the people to approach, and taught me how to build a business plan, find investors, and accomplish my goals. Without his help it would’ve taken me much longer. He knew how I could approach the woman in Topeka who ended up investing in Firecracker. Without that knowledge, I might not have found the financing I needed.

RR: It’s rare to hear a younger filmmaker talk about film with such disinterest. You seem to even dismiss the great films of the ‘70s - a decade that almost any film buff or critic will say produced some of the very best and most important films ever created. Don’t you think it would be at all beneficial to have your finger somewhat more on the pulse of what other filmmakers are doing and or to at least experience films that are considered the standards by which all should be measured?

SB: Mike Patton and I have discussed how people seem to miss this, but, when you are a heart surgeon and you spend all day in surgery, the last thing you want to do is come home and watch E.R.

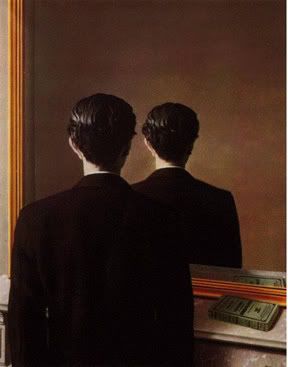

I don’t dismiss what Cassavetes did, or the others. I think what they did was great! But the raw realism he’s known for is not what I’m going for. If they don’t speak to me, they don’t speak to me. Inspirations for Firecracker were found in art, religion and fantasy. I would rather be inspired by a Magritte painting so much so that I build an entire cinematic sequence about a kid seeing the back of his head in a mirror. I don’t have to watch their movies in order to understand what I see and what I’m doing. Of course I’ve seen some movies made in the '70s. I appreciate any movie ever made but that doesn’t mean I have to like it. Sure, I can appreciate any movie, but to say they are the standard by which all others should be measured is false. There is no such thing.

I don’t have to watch their movies in order to understand what I see and what I’m doing. Of course I’ve seen some movies made in the '70s. I appreciate any movie ever made but that doesn’t mean I have to like it. Sure, I can appreciate any movie, but to say they are the standard by which all others should be measured is false. There is no such thing.

My self-assurance often comes off like arrogance, but when people take a moment to really listen, they understand it’s simply self-assurance. I don’t need to apologize for it.

RR: OK, Steve…I forgot about the “other” elephant in the room: I really, really disliked your movie and wrote a scathing – even borderline cruel – online review. I’ve even gone so far as to say that I do not even see what other people see in your movie (although clearly many see quite a bit). And I like weird movies, Steve. From a conceptual standpoint, Firecracker should be the kind of film that I sleep with a DVD copy of under my pillow at night. Aside from me being a possible dullard, do you have any theories as to why I do not “get” your movie? Is it at all important to you that anyone “get” and/or like your movie? If Firecracker hadn’t gotten raves from people like Ebert and mags like Film Threat, would you ever put up with a guy like me?

SB: I don’t like enabling a “what if” frame of mind. The facts remain what they are. If you define Ebert’s praise as validation what you are really saying is that you would need Ebert’s validation as the gauge for a success or failure. But, I define my own validation based on the fact I listened to myself and no one else (I was my own critic). Ross, you have the right to see whatever you want – never let anyone take that away from you.

I don’t make movies to please people. I make movies to be true to myself. So while I love that you dislike my movie, the idea of constructive criticism, like I mentioned earlier, doesn’t exist. I respect that you have an opinion especially if it’s true to who you are, but it doesn’t make a difference to me what your opinion is of my work directly. Your strong reaction to my work is wonderful, regardless!

I am not ashamed of my work and I'm never going to feel ashamed. I do not regret my work, nor do I regret anything I've done; nor do I feel that I should be blamed. I'm never going to deserve any kind of blame for continuing the art and culture of our time. I feel very confident in who I am personally and what my vision of any given subject is professionally. I know what my capabilities are. So I try and just focus on that. I can’t really control what goes on in other people, or how their perspectives contrast based on their own experiences or prejudices. I can just do the best job I can. There’s nothing I can do about how you see the world, art, other people or yourself.

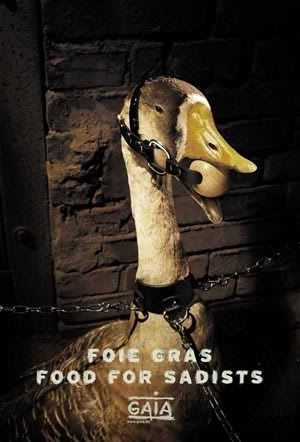

RR: You are bold and courageous, Steve; I honestly believe most filmmakers would have told me to fuck off – or even worse, ignore me altogether. What are we doing here and why are you giving me the time of day? SB: If everyone understood the laws of individual perception, there would be no conflict. You and I can have a conversation, for instance. PETA would understand that the geese at a foie gras farm do not see the world the way they do, and they could stand next to the farmers without having to get him to “see it their way.” Pro-Life people hiding outside the abortion clinic waiting to murder the doctors would go home because they would understand their views weren’t the right way and only way. I can go on and on.

SB: If everyone understood the laws of individual perception, there would be no conflict. You and I can have a conversation, for instance. PETA would understand that the geese at a foie gras farm do not see the world the way they do, and they could stand next to the farmers without having to get him to “see it their way.” Pro-Life people hiding outside the abortion clinic waiting to murder the doctors would go home because they would understand their views weren’t the right way and only way. I can go on and on.

I wanted to talk to you because it’s important that people really understand that every single person on this planet has their own individual viewpoint. It’s also important for artists to understand that no matter what you do there will always be people who hate you and hate what you’re doing, as well as people who love you and love what you’re doing. That is truth. Sometimes it’s fun to stir things up to get people thinking.

Perhaps most filmmakers would tell you to fuck off or cry their eyes out because they are insecure about their own viewpoints. Perhaps they are living in a two-dimensional view of the world. Will they begin to grasp the idea of individual perception? Or will they still exist in a world where they try to please everyone, where they define their perspectives based on what other people tell them to see, and use whatever measures necessary to insist that their view is the only one out there? We’ll see.

***********************************

“Your attitudes toward filmmaking are so far fucking out there that they deserve wider exposure.” – Ross to Steve in an e-mail dated Sept. 11th, 2006

There were probably a dozen different reasons I took Steve up on his interview offer, but chief among them was the above quote. You need look no further than the talkback for Part One of the interview to see that Balderson’s words can really piss people off. Most filmmakers are diplomatic in print or on a DVD commentary track; they may enlighten or bore, but they almost never make the blood boil.

Up until tonight, my intention was to write a third and final piece called "How I Learned to Stop Bombing 'Firecracker' and Love Steve Balderson". It would've been full of all sorts of philmic philosophizing and was intended to be about what I got out of this process...but the more I thought about it, the more it seemed pointless. I asked some questions, Steve answered them. The only thing that should be important is what the reader got out of it.

I still don't like Firecracker, and the Lynch accusations aside, I pretty much stand by my original thoughts. But after Steve dropped the nuclear bomb of its true cost, I've got a lot more respect for its visual aspects. For $300,000, it's a convincing looker of a period piece. And the talent he was able to get to rally behind his vision for next to nothing is most impressive. He's a true independent spirit successfully working outside the Hollywood system and he should continue avoiding that path. He's got a such a strong sense of what he wants, I'm not sure Hollywood would ever let him through the door anyway.

I do not consider myself a critic, even if others do. I live with a professional TV critic, and daily see the difference. I'm just a screenwriter with a blog and a desire to type opinions when I've got the time. Frankly, it's flattering that my words hit Steve hard enough to contact me in the first place. What's disturbing though, is it took an overwhelmingly negative review of someone's work to get a someone to contact me, as I don't particularly care to write negative criticism (which speaks of Firecracker's possible power). It's usually easier to pull something apart than it is to point out what's holding it together.

As entertaining as this has been, I'll be overjoyed the day I'm contacted by someone whose work I gushed about requests an interview. And if that person is Steve Balderson, I'll be even happier.

For some great thoughts on criticism, check out this recent piece from Jim Emerson's Scanners.

Thanks to Steve for hunting me down and offering the interview and to Don Walheim for dragging me to Austin to see Firecracker last November.